Posted on Dec 16, 2021

The death penalty in 2021 was defined by two competing forces: the continuing long-term erosion of capital punishment across most of the country, and extreme conduct by a dwindling number of outlier jurisdictions to continue to pursue death sentences and executions.

Virginia’s path to abolition of the death penalty was emblematic of capital punishment’s receding reach in the United States. A combination of changing state demographics, eroding public support, high-quality defense representation, and the election of reform prosecutors in many key counties produced a decade with no new death sentences in the Commonwealth. As the state grappled with its history of slavery, Jim Crow, lynchings, and the 70 th anniversary of seven wrongful executions, the governor and legislative leaders came to see the end of the death penalty as a crucial step towards racial justice. On March 24, Virginia became the first southern state to repeal capital punishment, and expanded the death-penalty-free zone on the U.S. Atlantic coast from the Canadian border of Maine to the northern border of the Carolinas.

Virginia’s historic abolition of the death penalty on March 24, 2021, highlighted the U.S.’s death-penalty erosion. The commonwealth — which from colonial times had carried out more executions than any other U.S. jurisdiction — became the first southern state to end capital punishment. Governor Ralph Northam, who endorsed abolition in his State of the Commonwealth address prior to the opening of the 2021 legislative session, said at the bill signing, “[t]here is no place today for the death penalty in this commonwealth, in the South, or in this nation.” The repeal effort emphasized the historical links between slavery, Jim Crow, lynchings, and the death penalty. Delegate Mike Mullin, the House sponsor of the bill, said, “We’ve carried out the death penalty in extraordinarily unfair fashion. Only four times out of nearly 1400 [executions] was the defendant white and the victim Black.” That history underlined the symbolic importance of the death penalty being abolished in the former capital of the Confederacy.

Further underscoring the relationship between death-penalty repeal and racial healing, Governor Northam on August 31 granted posthumous pardons to the Martinsville 7, seven young Black men who were tried, convicted, and sentenced to death in sham trials before all-white, all-male juries on charges of raping a white woman. They were executed in Virginia in 1951 in the largest mass execution for rape in U.S. history.

With Virginia’s abolition, a majority of U.S. states have now abolished the death penalty (23) or have a formal moratorium on its use (3). An additional ten states have not carried out an execution in at least ten years.

A judicial ruling in Oregon on October 8, 2021 is expected to clear much, if not all, of the state’s death row, rendering the death penalty functionally obsolete in the state. In 2019, the legislature narrowly limited the crimes for which the death penalty may be imposed. The Oregon Supreme Court, in its consideration of the appeal of death-row prisoner David Ray Bartol, found that his death sentence violated the state constitution’s ban on “disproportionate punishments” because the new law had reclassified his offense as non-capital. Because none of the people on Oregon’s death row committed crimes that are now defined as death-eligible, Jeffrey Ellis, co-director of the Oregon Capital Resource Center, said, “[m]y expectation is that every death sentence that is currently in place will be overturned.” Oregon has had a moratorium on executions for a decade, since then-Governor John Kitzhaber halted all executions on November 22, 2011.

Tennessee passed a bill closing a procedural loophole that had left death-row prisoners without any legal mechanism to enforce the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2002 ruling that the death penalty could not be used against people with intellectual disability. The bill, inspired by the case of Pervis Payne, created a post-conviction procedure for prisoners to file and obtain judicial review of claims that they are ineligible for the death penalty due to intellectual disability. Until this year, Tennessee law prevented death-row prisoners from presenting intellectual disability claims to state courts if their death sentences had already been upheld on appeal before the 2002 Supreme Court ruling. The bill was shepherded through the legislature by the Tennessee Black Caucus and passed with near-unanimous support. Lawyers for Payne, who is intellectually disabled and maintains his innocence, quickly filed a petition asking the Shelby County Criminal Court to “declare that Mr. Payne is ineligible to be executed because he is intellectually disabled.” After seeking for nearly 20 years to execute Payne without any judicial review of this issue, Shelby County prosecutors on November 18 conceded that he is intellectually disabled and not subject to the death penalty. They continue to oppose his innocence claim.

Efforts to restrict or abolish the death penalty gained traction in two states with Republican-controlled legislatures: Ohio and Utah. Governor Mike DeWine signed a bipartisan bill on January 9 making Ohio the first state to bar the execution of defendants who were severely mentally ill at the time of the offense. The new law granted current death-row prisoners one year to file mental illness claims, and in June, David Braden became the first person removed from death row under the new policy. In February, bipartisan sponsors announced a death-penalty repeal bill, which has received committee hearings in both houses. The legislative session continues in 2022, when legislators may vote on the bill.

Republican legislators in Utah announced in September that they will introduce an abolition bill in the 2022 session. Senator David McCay, a sponsor of the bill and a former death-penalty supporter, said of capital punishment, “It sets a false expectation for society, sets a false expectation for the victims and their families, and increases the cost to the state of Utah and for states that still have capital punishment.”

In both Virginia and Utah, prosecutors and family members of homicide victims took leading roles in advocating for the end of the death penalty. Four Utah prosecutors, representing counties that comprise nearly 60% of the state’s population, released an open letter in support of abolition. Salt Lake County District Attorney Sim Gill, Grand County Attorney Christina Sloan, Summit County Attorney Margaret Olson, and Utah County Attorney David Leavitt — two Republicans and two Democrats — called capital punishment “a grave defect” in the operation of the law “that creates a liability for victims of violent crime, defendants’ due process rights, and for the public good.” They highlighted concerns about innocence and racial bias and said the death penalty has an “inherently coercive impact” on plea negotiations. “A defendant’s need to bargain for one’s very life in today’s legal culture … gives already powerful prosecutors too much power to avoid trial by threatening death,” their letter states.

Twelve Virginia prosecutors, representing about 40% of the population, similarly joined calls for abolition. “The death penalty is unjust, racially biased, and ineffective at deterring crime,” they wrote in a letter to legislative leaders. “We have more equitable and effective means of keeping our communities safe and addressing society’s most heinous crimes. It is past time for Virginia to end this antiquated practice.”

Virginia’s abolition movement also gained legislative support as a result of the efforts of Rachel Sutphin, the daughter of Corporal Eric Sutphin, who was murdered in 2006. Sutphin had unsuccessfully sought clemency for William Morva, her father’s killer, based upon concerns about Morva’s mental illness. Sutphin told the legislators that victims’ family members are revictimized and repeatedly retraumatized by the appeal process and do not receive solace from the prisoner’s execution. In Utah, Sharon Wright Weeks, whose sister and niece were murdered by severely mentally ill cult leader Ronald Lafferty, is urging legislators to repeal and replace the state’s death penalty. Like Sutphin, she said her family was “retraumatized” by having to relive the murders in Lafferty’s first trial, throughout the appeals process, and then again in a retrial after his conviction was overturned. Lafferty ultimately died on death row.

By contrast, some states made efforts to resume executions by adopting brutal execution methods or distorting the legal process. Arizona announced in June that it had “refurbished” its gas chamber and would seek to carry out executions using cyanide gas, the same gas used by the Nazis to murder more than one million men, women, and children during the Holocaust. The announcement drew international backlash and condemnation.

South Carolina attempted to resume executions after a ten-year hiatus, scheduling one execution for February and another for May even though the state had no drugs to carry them out. The South Carolina Supreme Court vacated the execution notices and ordered the state to not issue another death warrant until one of three scenarios took place: the state confirms to the court that the Department of Corrections has the ability to carry out a lethal-injection execution, a death-row prisoner elects to be electrocuted instead, or the law changes to otherwise allow executions to take place. In response, the South Carolina legislature passed a bill in May 2021 making electrocution the default method of execution, with lethal injection or firing squad available as alternatives. The state immediately set two execution dates for June 2021, without having offered the men set for execution an opportunity to elect their method of execution. The South Carolina Supreme Court once again halted the executions, saying that the state had violated the prisoners’ “statutory right … to elect the manner of their execution.” The court also noted that the state had not yet developed a protocol for executions by firing squad and barred the state from setting any execution dates until a protocol is developed.

Prosecutors and state officials also engaged in questionable acts in 2021 that interfered with or undermined the legal process in death-penalty cases. Prosecutors secretly served as law clerks in cases they prosecuted without disclosing their conflicts of interest. Legislators in Nevada who worked full time as prosecutors blocked votes on an abolition bill opposed by their office. And officials in Florida, Missouri, Tennessee, and Oklahoma used their positions to attempt to intimidate parole board members or locally elected reform prosecutors or override their decisions.

Prosecutorial conflicts of interest were discovered in two separate cases this year, one in Texas and one in Tennessee. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals vacated the conviction of death-row prisoner Clinton Young because the prosecutor who tried him was simultaneously on the payroll of the judge who presided over the trial and decided Young’s trial court appeals. “Judicial and prosecutorial misconduct — in the form of an undisclosed employment relationship between the trial judge and the prosecutor appearing before him — tainted Applicant’s entire proceeding from the outset,” the court wrote. “The evidence presented in this case supports only one legal conclusion: that Applicant was deprived of his due process rights to a fair trial and an impartial judge.”

A similar problem appeared to be present in the case of Pervis Payne in Tennessee. In October, his attorneys sought a hearing to determine whether the Shelby County District Attorney’s office should be recused from his case because of an undisclosed conflict involving Assistant District Attorney General Stephen Jones. Payne’s attorney presented evidence suggesting that Jones may have represented the prosecution in Payne’s case while simultaneously working as a capital case staff attorney, assisting the county’s judges on death penalty cases during the time that Payne’s challenges to his conviction and death sentence were pending in the Shelby County courts.

Two Las Vegas prosecutors who hold legislative leadership positions in the Nevada state senate blocked movement on a death-penalty abolition bill in that state. Clark County District Attorney Steve Wolfson, who runs the office in which the two senators work when the legislature is not in session, was the lead witness against the bill in the Assembly. Over Wolfson’s opposition, the bill passed the state Assembly with a 26-16 vote and repeal advocates believed they had sufficient votes for passage in the Senate. However, they were unable to get a hearing or a vote on the bill in the Senate Judiciary Committee, which was chaired by Senator Melanie Scheible, a prosecutor in Wolfson’s office. Despite the significant margin for repeal in the state Assembly, Senate Majority Leader Nicole Cannizzaro, who is also a Clark County prosecutor, said legislators could not reach consensus on possible amendments, so the bill would not advance in the Senate. Shortly after the Assembly passed the bill, and while it was pending in the Senate, Clark County prosecutors filed pleadings to set an execution date for Nevada death-row prisoner Zane Floyd. Wolfson said the timing of the execution request was coincidental.

State officials across the country intervened to block the actions of locally elected prosecutors in several death-penalty cases. A Nashville judge approved a plea deal for the second time to resentence death-row prisoner Abu-Ali Abdur’Rahman to life without parole. Abdur’Rahman’s 1987 conviction was tainted by former Davidson County Assistant District Attorney General John Zimmerman’s unconstitutional use of discretionary strikes to remove African Americans from the jury. Abdur’Rahman had agreed to a plea deal with Davidson County District Attorney General Glenn Funk in 2019, but Tennessee Attorney General Herbert H. Slatery III intervened in the case, claiming that Funk and the trial court had no authority to vacate Abdur’Rahman’s sentence in the absence of a proven constitutional violation. Abdur’Rahman was procedurally barred from claiming jury discrimination in his case, Slatery said. After the Tennessee Court of Criminal Appeals struck down the first plea deal, Abdur’Rahman’s attorneys argued that new evidence of discriminatory jury selection allowed him to challenge his conviction. Funk agreed, telling the court that the state’s “interest in the finality of convictions and sentences is outweighed by the interests of justice, and in some situations by recognition of the sanctity of human life.” On December 10, Slatery announced he will not appeal the latest plea deal, finalizing Abdur’Rahman’s removal from death row.

In Missouri and Florida, state attorneys general intervened to block local prosecutors from advancing potential exonerations. Under a Missouri law passed in April 2021, county prosecutors may file motions to free prisoners they believe to be innocent. Jackson County Prosecutor Jean Peters Baker filed such a motion in the case of Kevin Strickland, who was capitally tried and ultimately sentenced to life without parole for a 1978 triple murder. Strickland’s innocence claims were supported not only by Peters Baker’s office, but by the two other men convicted of the crime, the lone eyewitness, and several state legislators. At a November hearing, the Jackson County Prosecutor’s office and the Missouri Attorney General’s office, which would typically be allied in a criminal case, were adversaries. In an attempt to prevent Jackson County prosecutors from presenting new evidence of innocence, the attorney general’s office filed a motion to limit the evidence the court could consider to the evidence that been presented to jurors in Strickland’s initial trial. When that failed, they moved to substitute themselves for local prosecutors as counsel for the state and to exclude Strickland from participating as a party in his own innocence hearing. The court rejected that motion as well and ultimately issued an order exonerating Strickland.

Florida Attorney General Ashley Moody also intervened in two cases involving potentially innocent death-row prisoners, filing motions to block DNA testing that State Attorney Monique H. Worrell had consented to and that the trial court had approved. Worrell had agreed to testing in the cases of Tommy Zeigler and Henry Sireci, both of whom were sentenced to death in 1976 for unrelated crimes and both of whom had consistently maintained their innocence for more than forty years. Moody argued that the state DNA law erected limits on when DNA testing could be performed and denied local prosecutors discretion to consent to DNA testing without the approval of state prosecutors, and that Ziegler’s and Sireci’s requests for testing did not meet the requirements of Florida state post-conviction law. She failed to note that years earlier, less sophisticated DNA testing had been conducted under a similar agreement without any objection from the attorney general’s office. The trial court refused to rescind its order, and Moody has further delayed the testing by filing an appeal.

In Oklahoma, prosecutors repeatedly attempted to manipulate the clemency process by trying to recuse members of the state’s pardons and parole board who they believed would favor death-row prisoner Julius Jones. In the spring of 2020, the pardons board indicated that it would be receptive to requests from death-row prisoners to consider petitions for commutation before death warrants had been issued in their cases. However, as a later investigation by The Frontier discovered, former judge Allen McCall — then a member of the board — had threatened the board’s executive director, Steven Bickley, with a grand jury investigation if he scheduled a hearing for Jones without first obtaining approval from then-Attorney General Mike Hunter. In June 2020, the board formally asked Hunter if it had the authority to conduct pre-warrant commutation hearings for death-row prisoners. Hunter agreed that the board had the authority to conduct such hearings, but Bickley subsequently resigned, saying he had been “threatened for doing his job.”

Prior to Jones’ commutation hearing, Oklahoma County District Attorney David Prater filed an emergency motion with the Oklahoma Supreme Court to recuse two members of the board, alleging that they would be biased in favor of commutation because of their ties to organizations that seek to reduce incarceration rates. The court denied the motion, writing that Prater was “asking this Court to provide for a remedy that simply does not exist under Oklahoma law.” The board voted 3-1 to recommend that Governor Kevin Stitt commute Jones’ sentence to a parole-eligible life term.

After that recommendation, Oklahoma Attorney General John O’Connor sought and obtained a death warrant for Jones. Governor Stitt then indicated he would not act on the board’s recommendation until it conducted a separate clemency hearing at which Jones and family members of murder victim Paul Howell would testify. Prior to that clemency hearing, O’Connor filed a new motion in the Oklahoma Supreme Court, attempting to recuse the same two board members on the same previously rejected grounds. The court again denied the recusal request and the board, once again by a 3-1 vote, recommended clemency. Four hours before Jones’ scheduled execution, Governor Stitt issued an order commuting Jones’ death sentence to life without parole, conditioned upon Jones never seeking a future pardon or further commutation of his sentence.

The change of presidential administration had major effects on the use of the federal death penalty, bringing Department of Justice (DOJ) practices back in line with those of other modern presidencies. The Trump administration concluded its unprecedented execution spree just four days before President Biden was inaugurated. The thirteen federal executions performed in a six-month period were procedurally and historically anomalous and marked the federal government as an outlier in its use of the death penalty.

Although Biden had campaigned on a promise to try to end the federal death penalty, his administration took no affirmative steps to do so. Attorney General Merrick Garland issued a memorandum announcing that DOJ would not seek new execution dates while it reviewed changes in death-penalty policies implemented under the former administration, but it also took steps to defend or reinstate federal death sentences in two notorious cases.

The executions of Lisa Montgomery, Corey Johnson, and Dustin Higgs in January 2021 concluded an unprecedented thirteen-execution spree undertaken by the federal government. In performing the executions, the Trump administration deviated dramatically from historical norms and practices. The six executions between the November 3, 2020 election and the January 20, 2021 inauguration were the most in U.S. history during a presidential transition period. The executions were performed during the worst pandemic in more than a century, flouting public health safeguards that led every U.S. state to pause executions. All 13 federal executions took place during the longest pause between state executions in more than forty years.

Throughout the federal execution spree, the conduct of the DOJ and the U.S. Supreme Court ran counter to both long-established norms and recent national trends. While death sentences and executions hovered near historic lows for the seventh consecutive year, and public support for the death penalty remained at its lowest level in half a century, the Department of Justice performed the most federal civilian executions in any single year since 1896. Among those executed were two people accused of murders committed in their teens, two prisoners with strong evidence of intellectual disability, two severely mentally ill prisoners, one prisoner who undisputedly was not the triggerman, and two prisoners who had contracted COVID-19 in the weeks leading up to their executions.

The Supreme Court intervened to lift stays and injunctions imposed by lower courts, foreclosing opportunities for judicial review of weighty claims of intellectual disability, competency to be executed, and challenges to the federal government’s execution protocol that the lower federal courts had found were likely to succeed. Four of the executions took place after the midnight expiration of the prisoners’ execution warrants, because the Supreme Court acted to lift lower court stays late at night. In those executions, the Federal Bureau of Prisons issued unprecedented and legally suspect same-day execution notices and proceeded to execute the prisoners within a few hours.

On June 30, Attorney General Merrick Garland announced a formal pause on all federal executions while the Department of Justice undertook a review of changes in executive branch death-penalty policies implemented under the Trump DOJ. The announcement marked the Biden administration’s official departure from the outlier practices of the Trump administration. “The Department of Justice must ensure that everyone in the federal criminal justice system is not only afforded the rights guaranteed by the Constitution and laws of the United States, but is also treated fairly and humanely. That obligation has special force in capital cases,” Garland wrote. The memorandum did not address the administration’s policy on continuing to seek new death sentences or oppose appeals filed by current death-row prisoners.

In the months after the announcement, the DOJ withdrew a number of notices of intent to seek the death penalty that had been filed under the previous administration. However, DOJ continued to defend previously imposed death sentences, and its actions in the cases of Dylann Roof and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev showed a willingness to do so aggressively, at least in the most nationally prominent federal cases. In August, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit affirmed Roof’s federal-court convictions and death sentences for the racially motivated murders of nine parishioners in an historic Charleston, South Carolina African-American church in 2017. The DOJ had defended Roof’s convictions and death sentences at the Fourth Circuit. In October, the U.S. Supreme Court heard oral argument in the case of Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, who was convicted of the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing. In 2020, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit had vacated Tsarnaev’s conviction, but the DOJ opted to continue the Trump administration’s appeal of that decision and argue in favor of reinstating the death sentence.

A White House spokesperson disassociated the President from the DOJ’s Tsarnaev appeal, citing the Justice Department’s “independence regarding such decisions.” In an email to reporters on June 15, Deputy White House Press Secretary Andrew Bates wrote, “President Biden has made clear that he has deep concerns about whether capital punishment is consistent with the values that are fundamental to our sense of justice and fairness. … The President believes the Department should return to its prior practice, and not carry out executions.”

Legislation to abolish the federal death penalty was introduced in the U.S. Congress, and legislators in both the House and the Senate wrote letters to Attorney General Garland urging him to stop seeking death sentences and asked President Biden to use his executive power to commute federal death row. The White House offered no substantive comment on either request.

Eddie Lee Howard, Jr., convicted and sentenced to death based on the false forensic testimony of a since disgraced prosecution expert witness, was exonerated in January 2021. He was the sixth death-row prisoner exonerated in Mississippi since 1973.

Howard spent 26 years on death row on charges that he murdered and allegedly raped an 84-year-old white woman. He was first convicted and sentenced to death in 1994 in a trial in which he represented himself. The Mississippi Supreme Court overturned that conviction in 1997 and ordered a new trial. He was convicted and sentenced to death again in a retrial in 2000 at which forensic odontologist Dr. Michael West testified that Howard was the source of bite marks he claimed to have found on the victim’s body during a post-autopsy, post-exhumation examination of her body. The initial autopsy report did not mention bite marks but claimed that the victim had been beaten, strangled, stabbed, and raped.

During post-conviction evidentiary hearings in 2016, Howard’s lawyers presented DNA evidence that eviscerated the prosecution’s false forensic testimony. DNA testing showed no evidence of semen or male DNA on the victim’s clothing, bedsheets, or body and no male DNA on the locations on the victim’s body where she supposedly had been bitten. None of the blood or other items tested contained Howard’s DNA. Male DNA found on the knife used by the murderer excluded Howard as the source.

Howard was represented by lawyers from the Mississippi Innocence Project and the national Innocence Project. “I want to say many thanks to the many people who are responsible for helping to make my dream of freedom a reality,” said Howard after his exoneration. “I thank you with all my heart, because without your hard work on my behalf, I would still be confined in that terrible place called the Mississippi Department of Corrections, on death row, waiting to be executed.”

In August 2021, Sherwood Brown was exonerated of a triple murder that sent him to Mississippi’s death row in 1995.

Brown was sentenced to death for the murder of 13-year-old Evangela Boyd and received two life sentences for the murders of her mother and grandmother. His convictions and death sentence rested in substantial part on false expert forensic testimony, as well as the perjured testimony of a jailhouse informant. The informant was facing serious charges for car theft when he claimed Brown had confessed to the murders. Prosecutors argued that blood found on the sole of one of Brown’s shoes came from the victims, and two forensic bitemark analysts falsely claimed that a cut on Brown’s wrist was a bitemark that matched the girl’s bite pattern.

DNA evidence later contradicted the prosecution’s narrative. The evidence showed that bloody footprints in and around the murder scene contained only female DNA and the blood spot on Brown’s shoe contained only male DNA. DNA testing on a swab of Boyd’s saliva did not contain Brown’s DNA, refuting the claim that she had bitten Brown. DNA tests on the sexual assault kit collected during the autopsy found no DNA from Brown but showed that Evangela Boyd’s pubic hair and her bra contained DNA from unidentified males. A forensic scientist from the Mississippi Crime Laboratory found that none of the hair evidence recovered from the clothing and bodies of the victims had any microscopic characteristics similar to Brown’s hair. A crime lab fingerprint analyst also found that none of the fingerprints found at the scene belonged to Brown.

Based on this evidence, the Mississippi Supreme Court overturned Brown’s conviction and death sentence in October 2017. However, Brown remained in custody facing possible capital retrial as prosecutors attempted to build another case against him. With Brown in county pretrial custody, four more laboratories tested the DNA evidence over the course of three more years. Each came back with the same results. “Every time, there was nothing incriminating Sherwood,” said one of Brown’s attorneys after his exoneration. “The state was trying to find something to incriminate Sherwood, but every time they did, it kind of stumped them deeper.”

Finally, on August 24, Mississippi Circuit Court Judge Jimmy McClure granted a prosecution motion to dismiss charges against Brown. He was released later that day after having spent 26 years on death row or facing the prospects of a capital retrial.

More than thirty years after a Florida judge sentenced him to death following an 8-4 sentencing recommendation by an all-white jury, Crosley Green was freed in April 2021. Citing Green’s age and health risks related to continued incarceration during the pandemic, a judge of the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Florida ordered Green’s immediate release while a federal appeals court considers prosecutors’ appeal of the district court’s July 2018 decision overturning his conviction.

Green, who is Black, was convicted and sentenced to death in 1990 for the 1989 murder of Charles “Chip” Flynn. No physical evidence linked him to the crime, and the one witness to the crime was the victim’s ex-girlfriend, who first responders initially identified as the likely perpetrator. The two police officers who responded to the crime scene told prosecutors they believed the ex-girlfriend had killed Flynn, but prosecutors withheld their notes from Green’s defense team, denying him access to potentially exculpatory evidence. All three witnesses who testified that Green had confessed to the murder later recanted their statements, saying they had been coerced by prosecutors. In 2007, the trial court overturned Green’s death sentence. The court found that trial counsel had failed to investigate court records that would have disproven the prosecution’s claim that Green had a previous conviction in New York for a crime of violence. The Florida Supreme Court upheld that ruling in 2008 and Green was resentenced to life before being released this year.

The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals (TCCA) in September 2021 vacated the conviction of death-row prisoner Clinton Young, whose prosecutor was also on the payroll of the judge who presided over the trial and decided his trial court appeals. In granting Young’s petition for a new trial, the TCCA wrote: “Judicial and prosecutorial misconduct — in the form of an undisclosed employment relationship between the trial judge and the prosecutor appearing before him — tainted Applicant’s entire proceeding from the outset. … The evidence presented in this case supports only one legal conclusion: that Applicant was deprived of his due process rights to a fair trial and an impartial judge.”

Young was convicted and sentenced to death by a Midland County jury in 2003 on charges that he had murdered two men for use of their vehicles during a 48-hour crime spree. He has long said he was framed for the murders. Assistant District Attorney Ralph Petty was one of the prosecutors in Young’s case, while at the same time serving as a paid law clerk to state District Court Judge John Hyde. In that dual role, Petty conducted research and made legal recommendations to the court on the same motions the prosecution had filed or were opposing in the case. Neither Petty, nor Hyde, nor the Midland County District Attorney’s office disclosed this conflict to the defense. Petty has since been barred from the continued practice of law.

After being directed by the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals (TCCA) to review Rodney Reed’s claim that he was innocent of the 1996 murder of Stacey Stites, a Texas district court judge recommended that Reed’s conviction be upheld. In a November 1, 2021 decision, Bastrop County District Court Judge J.D. Langley issued recommendations and findings of fact that credited every prosecution witness over every witness presented by Reed’s defense counsel.

The TCCA had stayed Reed’s execution on November 15, 2019, less than one week before he was scheduled to be put to death and returned his case to the Bastrop County district court to review Reed’s claims that prosecutors presented false testimony and suppressed exculpatory evidence and that Reed is actually innocent. The appeals court retained jurisdiction over the case and directed the trial court to make recommendations on how it should rule in the case.

During a ten-day evidentiary hearing, Reed’s lawyers presented evidence that Reed, who is Black, was having an affair with Stites, who is white; that Stites was actually murdered by her abusive fiancé, Jimmy Fennell; and that Fennell, who at that time was a police officer in Giddings, Texas, had framed Reed for the murder. Numerous witnesses testified that they had seen Stites together with Reed on prior occasions, heard Fennell threaten to kill her if she cheated on him, and heard Fennell admit to the killing. Two forensics experts testified that Stites died hours earlier than the prosecution had claimed, at a time that Fennell had said she was with him. Fennell took the stand and denied that he had committed the killing.

Langley accepted Fennell’s testimony on every disputed issue over the contrary testimony of a dozen separate defense witnesses. The court also rejected Reed’s challenges that prosecutors presented false forensic testimony, crediting the trial testimony of the prosecution’s local forensic examiners over that of Reed’s nationally known forensic experts. The county court transmitted its findings and recommendations to the TCCA, which will consider Judge Langley’s recommendation, but make its own final ruling. Reed’s lawyers continue to pursue relief, citing the unreliability of the evidence against Reed, as well as racial bias during his trial.

Dennis Perry was exonerated this year of the racially motivated murders of a deacon and his wife in a Black church in Georgia in 1985. His case was one of at least four death-penalty prosecutions involving misconduct by Brunswick Judicial Circuit Assistant District Attorney John B. Johnson III. Johnson obtained death sentences against death-row exonerees Larry Jenkins and Larry Lee, as well as Jimmy Meders, whose death sentence was commuted in 2020.

Johnson had capitally prosecuted Perry even after the lead investigators in the case had determined he could not have been at the church at the time of the murders. Johnson presented testimony from the mother of Perry’s ex-girlfriend, claiming he had told her he planned to kill one of the victims. Johnson withheld evidence from the defense that the witness was to receive $12,000 in reward money for her testimony. New DNA evidence implicated an alternate suspect, an alleged white supremacist who an Atlanta Journal-Constitution investigation showed had bragged that he had “killed two ni****rs“ and had manufactured a false alibi for the murders.

When he stood with his defense team on the steps of the Brunswick, Georgia courthouse after a trial judge dismissed all charges against him, Perry was a free man.

In November 2021, a Missouri judge released Kevin Strickland from prison more than 42 years after his wrongful capital murder conviction in June 1979. No physical evidence linked Strickland to the 1978 Kansas City triple murders for which he was convicted; two other men convicted of the killings later named other participants in the offense but said Strickland was not involved; and the lone eyewitness who testified against him said she had been pressured by police to falsely implicate Strickland.

Strickland initially rejected a plea deal in his case and faced a possible death sentence, believing the system would acquit him. At an innocence hearing authorized by a new Missouri law, he testified, “I wasn’t about to plead guilty to a crime I had absolutely nothing to do with. Wasn’t going to do it … at 18 years old, and I knew the system worked, so I knew that I would be vindicated, I wouldn’t be found guilty of a crime I did not commit. I would not take a plea deal and admit to something I did not do.” Strickland, who is Black, was capitally tried twice for the murders. The jury in his first trial deadlocked at 11-1 for conviction, with the only Black juror holding out for acquittal. Strickland was convicted of one count of capital murder and two counts of second-degree murder by an all-white jury in his second trial. After he was convicted, the prosecution withdrew the death penalty from his case.

Speaking to reporters outside the Western Missouri Correctional Center following his release, Strickland — now 62 and in a wheelchair following several heart attacks — said he was attempting to process a range of emotions. “I’m not necessarily angry. It’s a lot,” he said. “Joy, sorrow, fear. I am trying to figure out how to put them together.” He said he would like to become involved in efforts to reform the criminal legal system to “keep this from happening to someone else.”

Taxpayer payouts in 2021 from police and prosecutorial misconduct associated with the wrongful use or threatened use of the death penalty exposed a previously hidden collateral cost of capital punishment: the cost of liability. In 2021, multiple death-row exonerees won lawsuits against or received compensation awards from jurisdictions that wrongfully sentenced them to death, and multiple exonerees have lawsuits still pending against the jurisdictions and various officials involved in their wrongful convictions.

In May 2021, half-brothers Henry McCollum and Leon Brown were each awarded $31 million, $1 million for each year they spent in prison in North Carolina, plus an additional $13 million in punitive damages. McCollum and Brown were 19 and 15, respectively, when they were arrested in 1983 on charges of raping and murdering 11-year-old Sabrina Buie. They were coerced into confessing, and police fabricated evidence against them while suppressing or ignoring evidence of their innocence. In 2014, they were exonerated after DNA evidence implicated Roscoe Artis, who has been convicted of a similar crime. McCollum and Brown’s youth and intellectual disabilities made them particularly vulnerable to manipulation and coercion by police.

In August 2021, the Ohio Controlling Board voted unanimously to award Cleveland death-row exoneree Joe D’Ambrosio $1 million in compensation from the state’s wrongful imprisonment fund for his wrongful convictions. D’Ambrosio was convicted of burglary, kidnaping, felony murder, and the aggravated murder of teenager Tony Klann in 1989.

In early September 2021, former death-row prisoner Robert Miller reached a $2 million settlement with Oklahoma City for his wrongful conviction and death sentence for the rape and murder of two elderly women in Oklahoma County in 1988.

Both D’Ambrosio and Miller were tried and convicted in counties with long histories of prosecutorial misconduct and high rates of wrongful capital convictions. The compensation comes more than a decade after each was released from incarceration.

Multiple lawsuits brought by other death-row exonerees and exonerees who were threatened with the death penalty during their prosecutions are pending across the country. Former Mississippi death-row prisoner Curtis Flowers, who was exonerated in 2020, is suing the officials whose misconduct led to his arrest and repeated wrongful convictions. Flowers was tried six times and spent 23 years wrongfully incarcerated for a quadruple murder in a white-owned furniture store in Winona, Mississippi.

Florida death-row exoneree Robert DuBoise is suing the City of Tampa, four Tampa police officers, and the forensic odontologist who falsely testified against him, alleging that they fabricated evidence that led to his wrongful conviction and death sentence. DuBoise was exonerated in August 2020 after a Conviction Integrity Unit reviewed his case and new DNA evidence excluded him as the perpetrator of the rape and murder for which he was wrongfully convicted and sentenced to death 37 years earlier. DuBoise’s conviction was based on junk-science bite-mark evidence and false testimony from a prison informant.

In May 2021, Pennsylvania exoneree Theophalis Wilson filed a civil rights suit against Philadelphia following discovery by the Philadelphia District Attorney’s Conviction Integrity Unit that the prosecution’s lead witness had falsely testified against Wilson after homicide detectives threatened him with the death penalty. The Philadelphia Inquirer reported in June that the City of Philadelphia had paid $34 million since 2018 to six exonerees who had been wrongfully prosecuted for murder, and that 20 more people, including multiple death row exonerees, had either filed lawsuits or are within the statute of limitations to do so. On November 23, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit ruled in favor of former Philadelphia death-row prisoner Jimmy Dennis, who pleaded no contest to a murder he did not commit so that he could obtain his release from prison and avoid a possible capital retrial, that the police officers who withheld exculpatory evidence and planted evidence against him in his capital trial were not protected by qualified immunity for their actions.

Two nationally known prisoners with significant innocence claims, Julius Jones and Pervis Payne, were removed from death row in 2021 but remain imprisoned for life. On November 18, Oklahoma Governor Kevin Stitt commuted Jones’ death sentence to life without parole. That same day, the Shelby County District Attorney’s office conceded that Payne is intellectually disabled and ineligible for the death penalty. The trial court vacated his death sentence and removed him from death row on November 23.

Pervis Payne was convicted and sentenced to death in Memphis, Tennessee in 1988 on charges that he murdered Charisse Christopher and her 2-year-old daughter, Lacie, and seriously wounded her 3-year-old son, Nicholas. He was prosecuted by the Shelby County District Attorney’s office in a county that had the most known lynchings in the state of Tennessee and was responsible for nearly half of its death sentences. A July 2017 report by Harvard University’s Fair Punishment Project, The Recidivists: New Report on Rates of Prosecutorial Misconduct, highlighted Shelby County District Attorney Amy Weirich for withholding key evidence from the defense and making improper arguments.

The investigation and prosecution of Payne’s case was repeatedly infected by racial bias. Payne told his sister that while police were interrogating him, they said to him: “you think you black now, wait until we fry you.” In a trial tainted by prosecutorial misconduct, county prosecutors asserted without evidence that Payne, a young Black man, was on drugs and stabbed a white woman to death because she spurned his sexual advances.

Payne, the son of a minister, did not use drugs, and police refused his mother’s request to conduct a blood test to prove he had no drugs in his system. Prosecutors also falsely asserted that Payne had sexually assaulted Christopher, showing the jury a bloody tampon that they asserted he had pulled from her body. However, the tampon did not appear in any of the police photos or video taken at the crime scene. DNA testing of evidence that had been withheld from the defense for decades found the presence of an unidentified male’s DNA on the handle of the murder weapon. The testing found Payne’s DNA on the hilt of the knife, but not on the handle or any other location the killer’s hands would have been expected to touch while stabbing the victims more than 85 times.

The victims lived in an apartment across the hallway from Payne’s girlfriend. He has long maintained that he heard cries from the apartment and entered it to investigate. His lawyers said that evidence supports his testimony that he had touched the knife while trying to help the victims after the attack. Hearing police sirens, he then fled, fearing he would be considered a suspect.

For nearly two decades, prosecutors tried to execute Payne without any judicial review of his claim that he was ineligible for the death penalty because of intellectual disability. He was scheduled to be executed on December 3, 2020 but received a temporary reprieve from Governor Bill Lee based on coronavirus concerns. Responding to Payne’s case, the Tennessee legislature then amended the state’s post-conviction law to redress a flaw in the statute that had prevented death-row prisoners from presenting their intellectual disability claims to Tennessee’s courts. Payne became the first person to seek review under the new law, forcing prosecutors to finally address the issue. With a December 13 hearing date looming on Payne’s claim, the Shelby County District Attorney’s office conceded that he was ineligible for the death penalty.

Payne’s lawyers vowed to continue the fight to exonerate him. “Our proof that Pervis is intellectually disabled is unassailable, and his death sentence is unconstitutional,” said assistant federal defender Kelley Henry, Payne’s lead counsel. “The state did the right thing today by not continuing on with needless litigation. … We however will not stop until we have uncovered the proof which will exonerate Pervis and release him from prison.”

Julius Jones also was convicted and sentenced to death in a racially charged case tried by a prosecutor’s office notorious for misconduct. Jones, who is Black, was prosecuted by Oklahoma County District Attorney “Cowboy Bob” Macy, who sent 54 people to death row during his 21 years as district attorney.

Macy was featured among the rogue’s gallery of America’s Top Five Deadliest Prosecutors in a June 2016 report by the Fair Punishment Project. At that time, courts had found prosecutorial misconduct in approximately one-third of Macy’s death penalty cases and had reversed nearly half of his death sentences. DPIC’s February 2021 special report, The Innocence Epidemic, found that the five death-row exonerations in Oklahoma County — all a product of official misconduct and/or false accusation — were the fourth most of any county in the U.S.

Jones was convicted and sentenced to death by a nearly all-white jury for the 1999 killing of Paul Howell, a prominent white businessman. In his commutation application, Jones wrote that “while being transferred from an Oklahoma City police car to an Edmond police car, an officer removed my handcuffs and said; ‘Run n****r. I dare you, run.’” In a June 2019 sworn affidavit, one of the jurors in Jones’ case said she overheard another juror say, during a break, “something to the effect of, ‘They just need to take this n****r and shoot him, and take him and bury him underneath the jail.”

Jones and his family have long said he was at home with them playing Monopoly at the time of the murder. However, his court-appointed trial lawyers failed to call any alibi witnesses, did not cross-examine his co-defendant, Christopher Jordan, and did not call Jones to testify on his own behalf. An eyewitness description of the shooter matched Jordan’s appearance, not Jones’. Jordan made a deal with prosecutors to testify against Jones and served 15 years.

At a clemency hearing before the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board, one of Jones’ lawyers presented the board with additional evidence: testimony from Roderick Wesley. Wesley said that while in prison, Jordan confessed that he had killed a man and that someone else was doing time on death row for his crime. Jones’ prosecutors asked the Board to disregard Wesley’s testimony because of his criminal record. Noting the irony, Jones’ lawyer pointed out that while the prosecution asserted that defense witnesses with felony convictions are not believable, it “at the same time has asked you to credit the testimony of its central witnesses, all of whom were convicted felons and informants themselves.”

The Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board twice recommended that Jones’ sentence be reduced to life with the possibility of parole, based on evidence of Jones’ innocence. On September 13, and again on November 1, the board voted 3-1 to recommend clemency. On November 18, 2021, four hours before Jones’ execution was to be carried out, Governor Stitt commuted Jones’ sentence to life in prison without the possibility of parole. Stitt issued the commutation “on the condition that [Jones] shall never again be eligible to apply for, be considered for, or receive any additional commutation, pardon, or parole.”

Though there were fewer executions in 2021 than in any year since 1988, the executions that were carried out highlighted serious systemic issues concerning who is executed, how they are executed, and the legal process leading up to executions.

As in past years, the eleven people executed in 2021 represented the most vulnerable or impaired prisoners, rather than the “worst of the worst.” All but one prisoner executed this year had evidence of one or more of the following significant impairments: serious mental illness (5); brain injury, developmental brain damage, or an IQ in the intellectually disabled range (8); chronic serious childhood trauma, neglect, and/or abuse (9). In addition, Quintin Jones was executed in Texas for a crime he committed at age 20, placing him in a category that neuroscience research has shown is materially indistinguishable in brain development and executive functioning from juvenile offenders who are exempt from execution.

Compounding doubt about the reliability of the judicial process to correct constitutional errors, a groundbreaking new study found that at least 228 people executed in the modern era — or more than one in every seven executions — were put to death despite raising legal claims that the Supreme Court has said would require reversing their convictions or death sentences. Some of these prisoners were “right too soon,” raising meritorious claims before the Supreme Court had ruled on the issue. However, most of the prisoners were executed after the Supreme Court had established the basis for relief, when the lower state and federal courts refused to enforce the Supreme Court’s rulings and the Court declined to intervene.

The execution procedure itself raised significant concerns in multiple states, as Texas performed an execution without media witnesses present and Oklahoma began an execution spree, despite ongoing legal challenges to its lethal-injection protocol and a botched execution. The year’s executions also presented questions of innocence, competency to be executed, and executions carried out against the wishes of the victim’s family. The first three executions of the year were the final executions carried out by the Trump administration. In addition to the aberrant practices discussed at greater length in the Federal Death Penalty section, the three prisoners executed in January — Lisa Montgomery, Corey Johnson, and Dustin Higgs — each presented case-specific reasons why their executions would be inappropriate.

Lisa Montgomery, the first woman executed by the federal government in 67 years, had been the victim of lifelong sexual and physical abuse, including being sexually trafficked by her mother. The conditions of her pre-execution incarceration, including being denied underclothing while being watched by male prisoner guards, recapitulated her prior sexual victimizations, exacerbating her already severe mental illness. As she decompensated under the stress of the death warrant, Montgomery’s lawyers filed motions for a competency hearing, arguing that her “deteriorating mental condition results in her inability rationally to understand she will be executed, why she will be executed, or even where she is. Under such circumstances, her execution would violate the Eighth Amendment.” Montgomery received four separate stays of execution from federal courts. The stays were meant to provide time for the courts to consider whether the federal government had violated federal law in the way it set her execution date and to hold a hearing on her mental competency. Two of these stays remained in effect at the time of Montgomery’s scheduled execution. But, without issuing any explanation of its reasoning, the U.S. Supreme Court lifted the stays hours after Montgomery’s execution had been scheduled to take place. After the original notice of execution warrant expired at midnight on January 12, the Bureau of Prisons issued a new notice scheduling her immediate execution on January 13 and proceeded to execute her at 1:31 a.m.

The following day, the federal government executed Corey Johnson without any judicial review of his claim that he was ineligible for the death penalty because of intellectual disability. He was the second intellectually disabled person put to death in the 2020–2021 federal execution spree to be denied an opportunity to present evidence of disability. Judge James A. Wynn, dissenting from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit’s 8-7 denial of Johnson’s request for an evidentiary hearing, wrote, “Corey Johnson is an intellectually disabled death row inmate who is scheduled to be executed later today.” Newly available evidence, he wrote “convincingly demonstrates … that he is intellectually disabled under current diagnostic standards. But no court has ever considered such evidence. If Johnson’s death sentence is carried out today, the United States will execute an intellectually disabled person, which is unconstitutional.”

Dustin Higgs, the final prisoner executed in the federal execution spree, was put to death just four days before the inauguration of President Biden, who had expressed opposition to capital punishment. Higgs was the sixth person put to death during the transition period between former President Trump’s election defeat and Biden’s inauguration — the most transition-period executions in American presidential history. Higgs was sentenced to death based on the incentivized testimony of a co-defendant who received a substantially reduced sentence in exchange for his testimony. A third co-defendant, the undisputed triggerperson in the crime, was sentenced to life in prison. Higgs maintained that he did not orchestrate the crime, as alleged by prosecutors. The only evidence for prosecutors’ theory of the crime was the self-interested testimony of his co-defendant.

When Texas resumed executions on May 19, 2021, it ended a 315-day hiatus in state executions, the longest such gap in 40 years. Quintin Jones was put to death for the murder of Berthena Bryant, whose family opposed the execution. Bryant’s sister, Mattie Long, asked Governor Greg Abbott to spare Jones’ life, saying he had reformed his life and become a positive influence in the lives of others. Jones also sought a hearing on claims of intellectual disability. His IQ scores placed him in the borderline range of intellectual functioning, but his first state appeals lawyer could not develop the issue, because, at the time of the appeal, the Texas courts were applying an unconstitutionally harsh definition of intellectual disability. In seeking the hearing, Jones argued he should have an opportunity to have the issue decided based upon the current clinical diagnostic criteria for intellectual disability.

In a failure that Texas Representative Jeff Leach called “unfathomable,” Texas executed Jones without any media witnesses in attendance. It was the first time in the 572 executions Texas had carried out since 1976 that no media witnesses were able to serve as the public’s eyes on the state’s use of the death penalty. The Texas Department of Criminal Justice characterized the error as a “miscommunication” that resulted from “a number of new personnel” who were part of the execution team. In a statement, the Associated Press emphasized the importance of media witnesses, saying its reporters have, in recent years, witnessed and revealed to the public botched or problematic executions in Alabama, Arizona, Oklahoma, and Ohio.

John Hummel, an honorably discharged former Marine who experienced trauma during his military service, was executed in Texas on June 30. His court-appointed trial counsel, Larry Moore, failed both to present mitigating evidence concerning Hummel’s service and its effects on his mental health and to rebut testimony by prosecution witnesses who denigrated Hummel’s time in the service. Moore subsequently went to work for the Tarrant County District Attorney’s office while that office defended Hummel’s conviction and death sentence on appeal, filed motions to set his execution dates, and worked to have him executed. Hummel’s appellate lawyer, Michael Mowla, argued that Moore’s employment by the DA’s office presented a conflict of interest. State prosecutors argued that Moore had not been directly involved in its work on Hummel’s case but, Mowla wrote, Moore’s appeals had alleged that Moore had provided ineffective representation and, “[c]onsciously or not, Larry Moore and the Tarrant County District Attorney’s Office stand to benefit by hastening Hummel’s execution.”

Texas executed Rick Rhoades on September 28 while his lawyers were attempting to investigate whether prosecutors had unconstitutionally excluded jurors of color from serving on his case. Texas county, state, and federal courts denied Rhoades’ requests to produce juror records and stay his execution to provide time to litigate that claim. Like many other death-row prisoners, Rhoades experienced severe childhood trauma, which his attorneys said caused brain damage that impaired his judgment and impulse control. Rhoades was the first person executed in Texas after the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to hear John Henry Ramirez’s challenge to the state’s execution protocol, which alleged that the state would violate his religious liberty by barring his pastor from laying hands on him or praying aloud during his execution. Rhoades did not seek a stay on religious liberty grounds, providing a counterpoint to prosecutors’ contentions that death-row prisoners were simply filing such claims for “strategic delay.”

The next two executions, those of Ernest Johnson in Missouri and Willie B. Smith III in Alabama, demonstrated the difficulties prisoners face in advancing claims of intellectual disability. Despite the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2002 ruling in Atkins v. Virginia that it is unconstitutional to execute a person with intellectual disability, the two states proceeded with the executions of men with strong evidence that they were intellectually disabled. The Missouri Supreme Court applied medically unsound criteria in determining that Johnson was not intellectually disabled and refused his attorneys’ motion for a rehearing to apply current diagnostic criteria. In Smith’s case, a federal court agreed that he was intellectually disabled, but refused to retroactively apply two U.S. Supreme Court decisions that struck down rigid and unscientific standards like those Alabama’s courts had used to deny his claim. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit acknowledged that Smith’s execution was purely “a matter of timing”: if he had been tried today, he would not be eligible for the death penalty. Smith’s appeal lawyers also filed a claim that the state had violated the Americans with Disabilities Act by denying him accommodations in designating a method of execution. If Smith had understood that he would be executed by lethal injection unless he designated another method, they argued, he would have selected execution by nitrogen hypoxia.

Oklahoma resumed executions in 2021 after a six-year hiatus in the midst of federal litigation on the constitutionality of the state’s lethal-injection protocol. Oklahoma’s Attorney General and the federal judge overseeing the litigation had promised death row prisoners that no executions would be sought before the constitutionality of the execution process had been resolved. Nevertheless, with a pending February 2022 trial date in the federal lawsuit, the state issued seven death warrants, setting execution dates over a five-month period spanning October 2021 to March 2022. The state asserted that the prisoners for whom dates were set had no legal grounds to challenge the state’s execution process because they had not identified an alternative method by which they could be executed. The federal district court agreed and dismissed them from the litigation, but the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit reinstated them to the lawsuit on October 18.

The prisoners sought to enjoin their executions until the federal trial was resolved, but the district court denied their motion. The Tenth Circuit reversed and issued a stay, citing the inequity of executing prisoners using a method sufficiently problematic that a court had ordered a trial on its constitutionality. Prosecutors appealed, and just hours before John Grant’s scheduled execution on October 28, the U.S. Supreme Court, without explaining its reasoning, intervened to lift the stay.

Media eyewitnesses at Grant’s execution reported that he convulsed “about two dozen times” after midazolam — the controversial first drug in the execution protocol — was administered. Sean Murphy of the Associated Press said at a post-execution news conference that, after about two dozen full-body convulsions, Grant “began to vomit, which covered his face, then began to run down his neck and the side of his face.” Grant, he said, convulsed and vomited again. Another media witness, Oklahoma City Fox television anchor Dan Snyder, said that medical staff had to wipe away vomit multiple times during the execution. Contrary to the witnesses’ descriptions, Oklahoma Department of Corrections (DOC) communications director Justin Wolf claimed that the execution had been carried out “without complication.” DOC director Scott Crow called witness accounts “embellished,” adding that the state did not intend to change its execution protocol as a result of Grant’s execution.

Mississippi also resumed executions in 2021 after a long hiatus. In its first execution since 2012, Mississippi on November 17 executed David Cox, who had waived his appeals and “volunteered” to be put to death. Cox was at least the 150th volunteer executed in the modern era of the death penalty. Ten percent of all U.S. executions since the 1970s have involved volunteers, who comprised four of the first five prisoners executed after the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of capital punishment in 1976, and were the first prisoners to be executed in 15 states and by the federal government. Cox’s execution marked the sixth time a state restarted executions after a pause of between five and 21 years by acceding to the wishes of a volunteer.

The final execution of the year, that of Bigler “Bud” Stouffer in Oklahoma, took place despite the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board’s recommendation that his sentence be commuted to life without parole. Board members expressed concerns about the botched execution of John Grant. Larry Morris, one of the three board members who voted for clemency, said, “I don’t think that any humane society ought to be executing people that way until we figure out how to do it right.”

In addition to the problematic executions carried out in 2021, a groundbreaking new study found that nearly 15% of all executions between the 1970s and June 30, 2021 — or more than one in seven — involved cases in which U.S. Supreme Court caselaw now clearly establishes the unconstitutionality of the conviction or death sentence. In Dead Right: A Cautionary Capital Punishment Tale, published in the Fall 2021 issue of the Columbia Human Rights Law Review, Cornell Law School professors Joseph Margulies, John Blume, and Sheri Johnson reported that 228 executed prisoners “had claims in their case that today would render their execution unconstitutional.”

These executions fell into two major categories: (1) people who were executed before the Supreme Court categorically barred applying the death penalty against defendants who shared their characteristics; and (2) people who were executed despite raising claims the Supreme Court has clearly said establish the unconstitutionality of their convictions or death sentences. In the first category, the researchers found 22 people who were younger than age 18 at the time of the offense who were executed before the Supreme Court limited the death penalty to offenders 18 or older in Roper v. Simmons in 2005. They also identified at least 42 people with intellectual disability who were executed before the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the use of capital punishment against those with intellectual disability in 2002. In the second, larger category, they identified 173 individuals who presented claims that the U.S. Supreme has recognized clearly establish the unconstitutionality of their convictions or death sentences. Those 173 included 170 people who were executed after the Supreme Court had established the basis for relief in their cases when the lower state and federal courts refused to enforce the controlling Supreme Court caselaw and the Supreme Court refused to intervene. Subtracting the individuals who fell into multiple categories, the professors found 228 executed prisoners who were “right too soon.”

The worst offenders were the states of Texas, in which “at least 108 people were executed after the Supreme Court had already established the relevant basis for relief,” and Florida, which has executed at least 36 prisoners despite Supreme Court decisions clearly establishing the unconstitutionality of the individuals’ death sentences. That amounts to 36.4% of all Florida executions (1 in every 2.75 executions) and 18.8% of all Texas executions (1 in every 5.3 executions).

The 2021 executions also demonstrated the continuing geographic arbitrariness of the death penalty. Just five U.S. counties — Harris, Dallas, Tarrant, and Bexar in Texas and Oklahoma County in Oklahoma — have accounted for 20.9% of all U.S. executions since the 1970s. With two executions in cases from Tarrant County in 2021 and one each from Harris and Oklahoma counties, these outliers accounted for 36.4% of the year’s executions.

2021 was a deadly year for death-row prisoners with intellectual disability. At least seven intellectually disabled prisoners faced death warrants at some point in 2021. Three were executed; three came within eight days of being put to death before their executions were stayed; and one faces execution in January 2022. A U.S. Supreme Court seemingly devoted to undermining the constitutional protections afforded by Atkins v. Virginia denied stays of execution or vacated grants of penalty relief for four intellectually disabled men and refused to review the case of another even though prosecutors agreed he was ineligible for execution.

The year began with the execution of Corey Johnson, who was put to death by the federal government on January 14, 2021 without judicial review of his strong evidence of intellectual disability. He was the second intellectually disabled person executed in the federal government’s 2020-2021 execution spree, following by one month the December 11, 2020 execution of Alfred Bourgeois.

Missouri executed Ernest Johnson on October 5 after applying a medically inappropriate and unconstitutionally restrictive definition of intellectual disability to deny his challenge to his death sentence.

Barely two weeks later, Alabama executed Willie B. Smith III on October 21 despite a federal appeals court’s acknowledgement that he met the clinical criteria for intellectual disability. Saying if he had been tried today, Smith would be ineligible for the death penalty, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit refused to retroactively apply two U.S. Supreme Court decisions that demonstrated the unconstitutionality of Alabama’s rejection of his intellectual disability claim.

On July 2, in a ruling rendered along partisan lines without benefit of oral argument, the United States Supreme Court overturned a federal appeals court decision that had vacated the death sentence imposed on Alabama death-row prisoner Matthew Reeves, whose trial lawyers had failed to obtain expert assistance to present evidence of his intellectual disability. Alabama has scheduled Reeves’ execution for January 27, 2022.

In a November 1 ruling that provoked a sharp dissent from the Court’s liberal minority, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to review the case of federal death-row prisoner Wesley Coonce, whom prosecutors and defense lawyers agreed is not eligible for the death penalty. Coonce became intellectually disabled at age 20 after sustaining a traumatic brain injury that caused bleeding around his brain and temporarily left him comatose. Intellectual disability is a developmental disorder that requires onset “during the developmental period,” which historically had been defined as age 22. When Coonce was tried, however, the diagnostic criteria employed by the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disability (AAIDD) required that the disorder manifest before age 18. Because of that, the trial court and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit refused to consider his evidence of intellectual disability. While his petition for review was pending in the Supreme Court, the AAIDD revised its age-of-onset criterion to return to age 22. Dissenting, Justice Sotomayor wrote: “To my knowledge, the Court has never before denied a [request to grant certiorari, vacate the lower court’s decision, and remand the case to a lower court for further review] in a capital case where both parties have requested it, let alone where a new development has cast the decision below into such doubt.”

Several state supreme courts have also taken steps to undermine or evade Atkins’ constitutional prohibition on executing individuals with intellectual disability. On June 1, the Georgia Supreme Court denied a constitutional challenge by Rodney Young to the state’s harshest-in-the-nation statutory requirement that a capital defendant must prove beyond a reasonable doubt that he or she is intellectually disabled before being declared ineligible for the death penalty. Under the beyond-a-reasonable-doubt standard, no Georgia jury has ever found a defendant charged with an intentional killing to be intellectually disabled.

On March 18, the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals upheld Alton Nolen’s death sentence against a challenge that he was ineligible for the death penalty because of intellectual disability. Viewing the evidence in the light most favorable to the prosecution, the court held that the jury was entitled to credit the testimony of the prosecution’s expert witness, who did not administer any tests of intellectual or adaptive functioning but criticized the defense experts’ testing methodology and conclusions.

Texas state courts also applied medically inappropriate and unconstitutionally restrictive definitions of intellectual disability to deny claims by Blaine Milam, Edward Busby, and Ramiro Ibarra that they were ineligible for the death penalty. Milam and Busby came within a week of execution before the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals (TCCA) stayed their executions (January 15 and February 3, respectively) and ordered that their claims be properly reviewed. Ibarra received a stay from the appeals court on similar grounds on February 24, eight days before his scheduled execution. The TCCA previously reversed Charles Brownlow’s death sentence, saying that the state courts had applied an unconstitutional definition of intellectual disability to reject his claim. On remand, the Kaufman County District Attorney’s office on January 22 conceded that Brownlow is intellectually disabled.

Pervis Payne was one of 14 Tennessee death-row prisoners with active death sentences who could not obtain judicial review of their intellectual disability claims because of defects in the state post-conviction review system. He was scheduled to be executed on December 3, 2020 but received a temporary reprieve because of coronavirus concerns on November 6, 2020. The Tennessee legislature subsequently amended the state post-conviction process to make review available. The Shelby County District Attorney’s office, which for nearly two decades after Atkins had attempted to execute him, conceded in November 2021 that he is ineligible for the death penalty. His death sentences were vacated on November 23. He had been on death row for 33 years.

On August 31, Los Angeles prosecutors agreed that Stanley Davis, who was sentenced to death in 1989 for a double murder that occurred in 1985, was intellectually disabled, bringing to end what District Attorney George Gascón characterized as “more than 30 years of costly litigation.” In Florida, a Marion County judge accepted a stipulation that Sonny Boy Oats, who had been on death row for more than 40 years, was ineligible for the death penalty because of intellectual disability. Thirty years earlier, during a hearing to vacate his death sentence because his trial counsel had failed to investigate and present evidence of what was then known as mental retardation, prosecutors had conceded that Oats met the diagnostic criteria for intellectual disability. The trial court nonetheless denied Oats’ ineffectiveness claim. After Atkins was decided in 2002, Oats again sought to overturn his death sentence, but the trial court refused to consider Oats’ evidence from the 1990 hearing. In 2015, noting that “expert after expert consistently recognized that Oats has an intellectual disability,” the Florida Supreme Court ordered a new evidentiary hearing on the issue. In February 2020, prosecutors again agreed that Oats is intellectually disabled, but because of the COVID pandemic, it took until April 2, 2021 for Oats to be resentenced to life.

In a contested case, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit on August 13 affirmed an Arkansas district court decision that granted Alvin Jackson relief under Atkins. The appeals court denied Arkansas prosecutors’ motion for reargument on October 20.

The eighteen death sentences imposed in 2021 again disproportionally involved cases that lacked key trial protections or classes of the most vulnerable defendants. They included three prisoners sentenced by non-unanimous juries, two who waived jury sentencing, and another who expressed a desire to be executed. As in past years, they were concentrated in a small number of high-use states. Though the year’s sentencing numbers were artificially reduced as a result of ongoing pandemic-induced court closures and trial delays, the record-low number of new death sentences also unquestionably reflected declining public support for capital punishment and the policies of reform prosecutors who have chosen not to pursue the death penalty.

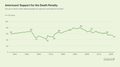

The 2021 Gallup poll measured public support for the death penalty at a half-century low, with 54% of respondents to the organization’s annual crime survey saying that they were “in favor of the death penalty for a person convicted of murder.” The figure was the lowest since 50% of respondents in March 1972 told Gallup they favored the death penalty and matched the record-low 54% of Americans in the May 2020 Gallup Values and Beliefs Poll who said the death penalty was “morally acceptable.” Gallup described the results as “essentially unchanged from readings over the past four years.” Support was marginally lower than the 55% reported in October 2017 and 2020, and two percentage points lower than in October 2018 and 2019.

Support for capital punishment has declined 26 percentage points from the high of 80% reported in Gallup’s September 1994 crime survey.

Forty-three percent of respondents told Gallup that they were opposed to the death penalty as a punishment for murder, matching the responses reported in the 2020 death penalty poll. Opposition to capital punishment was at its highest in 55 years, since 47% of Americans expressed opposition to capital punishment in the May 1966 Gallup survey. The number was marginally higher than the 42% level of opposition reported in 2019 and two percentage points higher than in 2017 and 2018.

A poll conducted in April 2021 by the Pew Research Center also reported a decline in public support for the death penalty. However, because of changes in its polling methods, Pew’s reported level of death-penalty public support was higher than Gallup’s. In a Pew phone survey in August 2020, 52% of adults said that they favored the death penalty, while 65% of online respondents favored the death penalty. Saying that “survey questions that ask about sensitive or controversial topics — and views of the death penalty may be one such topic — may be more likely to elicit different responses across modes,” Pew shifted to exclusive reliance on online polling in 2021. Its online polling found that 60% of respondents said they favored the death penalty for persons convicted of murder, a five percentage-point decline from the levels of support reported by online respondents in August 2020 and September 2019.